Frederick Douglass Black and White Pic 1863 Ladies Fashion

[NOTE: This essay page is currently being reformatted; please exist patient every bit nosotros revise.]

"Truthful Pictures": Frederick Douglass on the Promise of Photography

Gregory Fried, Suffolk University

Human is the only moving picture-making brute in the world. He alone of all the inhabitants of the globe has the chapters and passion for pictures . . . Poets, prophets, and reformers are all motion picture-makers, and this ability is the surreptitious of their ability and achievements: they see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the

contradiction. —Frederick Douglass

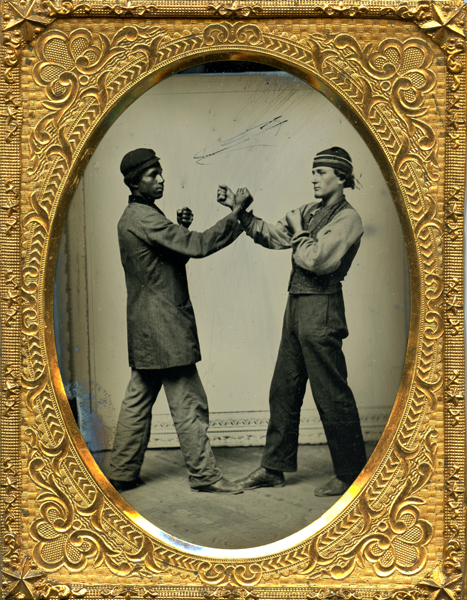

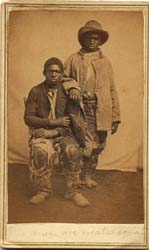

Figure 1: Unknown photographer, 2 boxers, ambrotype (circa 1860), collection of Greg French.

In the late summer of 1839, at an extraordinary articulation meeting of the Academy of Science and the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre presented to the public and to the world the first truly successful photographic process: the daguerreotype. It is difficult for u.s.a. to grasp now, later more than than 170 years of photography, the astonishment and enthusiasm that greeted Daguerre's discovery. On a small plate of metal, Daguerre coaxed the sun'southward rays, guided by the lens of a camera, to produce an image whose detail was as minutely true-blue to reality every bit the reflection in a mirror—just in black and white. In an age of soaring expectations for science, the daguerreotype symbolized the possibility that human ingenuity might capture the very essence of nature.

The daguerreotype is truly a marvel: strictly speaking, it is impossible to reproduce one, since a daguerreotype image sits on a argent surface that reflects like a mirror; i therefore sees oneself in the image, too. The only fashion to appreciate a daguerreotype properly is to see it, equally information technology were, in person. This personal intimacy and immediacy lent much of the fervor to what Frederick Douglass called the new "passion for pictures." While the inventor of the daguerreotype was a Frenchman, nowhere did this passion catch on equally it did in the still young United states of america. For Douglass, the quondam slave and abolitionist orator, photography, as a mirror of reality, would serve as a new weapon in the fight for liberty and human dignity.

Samuel F. B. Morse, the American inventor and painter, happened to be in Paris in 1838–39 to promote his own invention, the electromagnetic telegraph. In that location he met and befriended Daguerre. Morse tried his hand at the process every bit presently as Daguerre made it public, and, on his return to the States, he successfully spread word of Daguerre's genius to his fellow Americans. Scores, then hundreds, and finally thousands of American practitioners took up the fine art, improving the technique so apace that by the early 1840s a proficient daguerreotypist could earn a respectable income as a portraitist. The American public hungered unrelentingly for portraits.

Douglass explains this passion well: "The great discoverer of modernistic times, to whom coming generations will award special homage, will exist Daguerre. Morse has brought the seeds of the world together, and Daguerre has made it a motion picture gallery. Nosotros have pictures, truthful pictures, of every object which can interest united states of america . . . What was in one case the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and keen is now the privilege of all. The humblest servant daughter may now possess a picture of herself such every bit the wealth of kings could not purchase 50 years ago."

Past the 1850s and 1860s, American ingenuity had led to an explosion of photographic techniques including the ambrotype, tintype, and carte-de-visite—all to feed the endless American appetite for portraits. Tens of millions of images were produced. Once, portraiture had been the "special and sectional luxury" of the rich or the noble in the form of paintings or sculptures that cost a small fortune to commission; at present Americans could assert their egalitarianism in self-representation. For less than a solar day'due south wages, even a humble housemaid could confirm her dignity and make her bid for immortality (fig. two).

Figure 2: Bearding photographer, three housemaids, tintype (circa 1870s), collection of Gregory Fried.

As Frederick Douglass saw it, Morse and Daguerre were two facets of the same democratizing revolution, a revolution that was fast uniting the world in communication (Morse) and in image (Daguerre). For Douglass, this universalizing and democratizing revolution involved more than a breaking down of class divisions; information technology also meant attacking what nosotros might telephone call the optics of racism, that is, how white Europeans had come to run across black Africans equally a nearly separate species, a view that corrupted painted portraits: "Negroes tin can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists. Information technology seems to u.s. side by side to impossible for white men to take likenesses of black men, without nearly grossly exaggerating their distinctive features. And the reason is obvious. Artists, like all other white persons, have adopted a theory respecting the distinctive features of Negro physiognomy." When Douglass complained about how white artists "accept likenesses" of blacks, he meant painters, sculptors, and engravers—all artists except photographers, because in all other art forms, the creative person'due south preconceived way of seeing necessarily intrudes upon the representation of the subject matter. In voicing this complaint, Douglass echoed a widely held notion about photography, 1 that persists to this 24-hour interval: that unlike other techniques in art, photography is a true mirror of nature whose method, because it relies on the nonpartisan effectiveness of rays of light rather than the mitt of homo beings, tin can present us with what Douglass called "truthful pictures" of reality.

Many contemporary theorists would now question that assumption. They would claim that photography is more fine art than science by pointing to how the discipline thing is arranged, how the lighting is manipulated, what type of lens or printing-out paper is employed, even to the way the scene is equanimous and framed. All these factors play as much of a subjective role in producing and seeing the work of art as does the manus of the artist with a paintbrush or a mallet and chisel. The photograph, and so, is no more a "true picture" of reality than a cubist painting by Picasso.

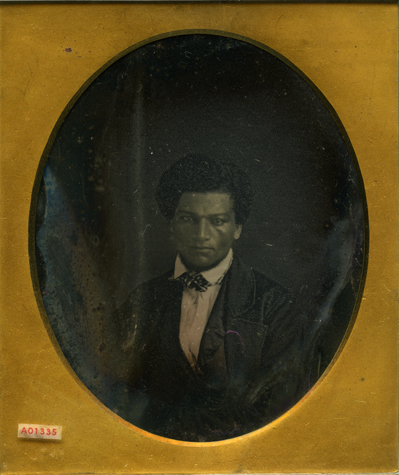

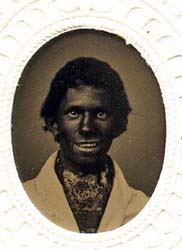

But, at least for now, let us give Douglass the benefit of the doubt. After all, there is for most of u.s., in our pre-theoretical experience of photography, something of that feel of immediacy and revelation of reality that and then astonished and inspired him, equally well every bit and so many other Americans, a century and a one-half ago. Douglass was photographed frequently. Ane of the very primeval known portraits of him was taken in the mid-1840s, probably just around the fourth dimension the 1845 publication ofThe Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave Written by Himself made Douglass a national and then an international celebrity. This austere portrait (fig. 3) of the withal youthful Douglass, who meets our gaze then forcefully, epitomizes his hope and expectation that photography might bestow a public dignity upon African Americans that would provide a pictorial argument for their inclusion in the promise of the Declaration of Independence: that the simply legitimate government is 1 that gives support to the self-axiomatic truth that all men are created equal.

Figure three: Anonymous photographer, Frederick Douglass, sixth-plate daguerreotype (circa 1845), collection of Greg French.

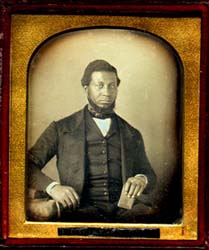

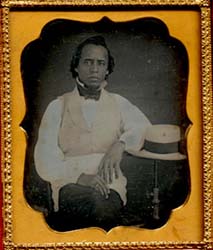

Many other portraits make a like visual argument, such equally this 1 of an unnamed self-confident keyed bugle histrion (fig. 4).

Figure 4: Anonymous photographer, man with keyed bugle, daguerreotype (circa 1845), collection of Greg French.

The portrait of this man, with his sophisticated instrument and sail music, proclaims his capacity for refinement and cocky-cultivation. Or consider this portrait of an unidentified African American woman whose strength and resilience break through the stiff pose of conventional portraiture (fig. 5):

Figure five: Anonymous photographer, adult female in tinted wearing apparel, daguerreotype (late 1840s), collection of Greg French.

These portraits, and others such equally this one of a man holding a book, prove sitters who have attained something like centre-course respectability (fig. vi).

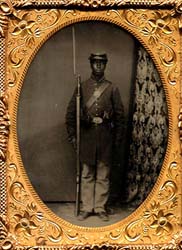

met the call to artillery (fig. 9).

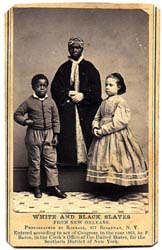

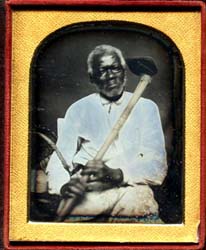

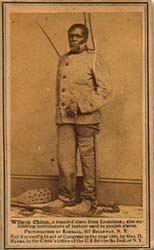

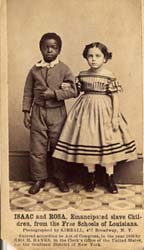

Fig. 12. Lensman unknown:Wilson [Chinn], Charley, Rebecca, and Rosa ("Learning Is Wealth"), carte-de-visite, c. 1863. Collection of Greg French.Some images present difficulties for Douglass's hope that photography would serve equally an unambiguous language of freedom. For example, consider this portrait of a slave from Missouri (fig. 13).

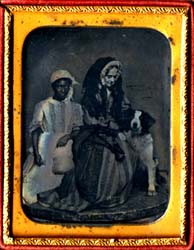

the line betwixt black and white (figs. 16, 17, 18).

Was Frederick Douglass naive to hope for a revelation of human dignity from photography? Only if we believe that the failures of the past must exist our failures, also. We can look advisedly at these portraits. We can search in them for the echoes of man presence. We can affirm, gloat, and restore the subconscious, the neglected, and the bearding. In this style, their past can be our nowadays. And our time to come. Douglass said that we tin can "see what ought to exist by the reflection of what is, and endeavour to remove the contradiction," and surely it is non too tardily for idealism like that. We are still the picture-making animate being that can envision a future past seeing the present clearly in reflection on the past.

***

The author wishes to thank his colleague and friend, Greg French, for permission to employ so many images from his collection. This essay originally appeared in the online journal Common-place, vol. ii, no. two, January 2002, and is reprinted here with permission.

Farther Reading:

See F. James Davis, Who Is Black? One Nation'due south Definition (Academy Park, Pennyslvania, 1991); Frederick Douglass, "Life Pictures," holograph dated 1861, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Library of Congress, microfilm accretion no. 16377, reel 14, frames 394–412; Frederick Douglass, "Pictures and Progress," in John W. Blassingame, ed., The Frederick Douglass Papers, ser. one, vol. 3 (New Oasis, 1979–92); Merry A. Forresta and John Woods, eds., Secrets of the Dark Chamber: The Art of the American Daguerreotype (Washington, DC, 1995); O. Henry Mace, Collectors' Guide to Early on Photographs, 2d ed. (Iola, Wisconsin, 1999); Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York, 1993); Beaumont Newhall, The Daguerreotype in America, 3d ed. (New York, 1976), and The History of Photography, 5th ed. (New York, 1994); John Stauffer, "Race and Gimmicky Photography: Willie Robert Middlebrook and the Legacy of Frederick Douglass," in John Wood, ed., The Journal of Contemporary Photography: Civilisation and Criticism (Brewster, Massachusetts, n.d.); Colin Westerbeck, "Frederick Douglass Chooses His Moment" in Susan F. Rossen, ed., African Americans in Art (Chicago, 1999).

0 Response to "Frederick Douglass Black and White Pic 1863 Ladies Fashion"

Post a Comment